The Story Of The Jane Lowden

This sea

chest displayed in the museum is believed to be that of Captain Casey.

This sea

chest displayed in the museum is believed to be that of Captain Casey.

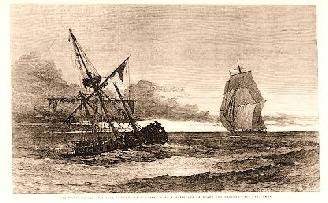

Shows the Jane Lowden stormbound. From engraving

London Illustrated News.

See below for the story:

Notes to accompany the story as told by Capt John Casey of Padstow and reported in contemporary newspapers.

The account published in The World Wide Magazine 1899 and that published earlier in small booklet form are essentially the same. The latter was reprinted in the Padstow Echo in December 1971. It is interesting to find the story surface in 1899 some 32 years after the event and 19 years after the death in Padstow of John Casey.

Using census returns I attempted to check out crew members I thought may have come from the Camel River area. Some crew lists are available at the CRO Truro and from them I identified James Beatt sailing with Capt Casey on the Jane Lowden on an April trip in 1864 to Quebec as a ship’s carpenter – wages £5.10 per month – this was 10 shillings more than the mate got, reflecting the importance of the post. His birthplace was Anstruther Scotland. However I had found him living in Church St Padstow in 1851 with a Padstow born wife Mary (31) two daughters and a son. Having key members of the crew familiar with the ship and known to the Captain must have been important to the smooth running of the vessel.

John Russell Beatt, son of the carpenter, was living in High St Padstow in 1881 as a Customs Officer with his wife Johannah (33) and family. I would not be surprised to find links through marriage with present day families in the town.

The Mate, Edwin Mabley, had also sailed with Capt Casey on at least one previous voyage in August 1864; his place of birth, Wadebridge. This family name sometimes spelt Mably continues in the area but no direct link has been found.

James Bird, second mate - In 1871 there was Ellen Bird (29)

a widow living in Padstow. More research is needed.

John Avery, cook and steward - certainly there

have been Avery’s in Padstow but I did not trace a link.

Of the 8 AB’s listed, Evan Davis, John Pugh, William Thomas, and Thomas Bowen came from the port of departure Milford Haven. (Pembrokeshire Herald Feb 1866) as did the boy James Griffiths - listed as Griffin elsewhere. Francis Martin, Wm Maitland and Hugh Rice are not mentioned in this report

Here Mabl(e)y is spelt Malby, a native of Cornwall and a John Cuew is named but not on other lists. The Boatswain is named as Samuel Bird, (James on other list); native of Padstow and the cook and steward from Padstow is given as John Henry (Avery on other list). In this report John Connolly is named as a seaman of Scotland and a boy named Thomas Gate could be Thomas Geake, on the other list, a known Cornish name as is Henry Pope.

We learn from this South Wales news report some extra poignant details – ‘Pugh who had married a fortnight before sailing was drowned’. Thomas ‘called on his mother to shut the door to keep out the cold’.

To find a little more on the background of John Casey’s life I look to marriage records which show him married to Eliza Buse aged 24 in Padstow in 1852. He is 22 and a native of Wexford Ireland, she a dressmaker daughter of John a sailor. The family story has it that he ran away to sea. On the marriage certificate his father’s occupation is given as a weaver.

In 1861 Eliza (32) is following her trade in Duke St Padstow living with her mother Sarah Buse (48) and daughters Maria Louisa (7) Sarah Ann (5) and Eliza Mary (1).

According to the Captains’ Register John Casey was on the Padstow registered INTREPID at this time plying the emigrant trade to North America.

After the wreck some time in 1866 John Casey was reunited with his family in Padstow. One report suggests he relied on charity to pay his fare home. He was 35 and as far as we know, never went to sea again.

In 1871 aged 40 he is at home in Padstow with five daughters aged from 17 to 5 days and one year old John. The eldest son Edward Buse aged 8 was away at the time of the census. He had interests in several ships along with his brother- in- law Henry Buse, including the MARIA LOUISA bought for him by public subscription and named after his eldest daughter. Henry Buse is named in Ships of North Cornwall by John Bartlett as the owner of the Tredwen, Padstow built IDA ELIZABETH named after the Dutch ship that picked up Capt Casey.

John Casey died on June 19th 1880 aged 49 and is buried in Padstow Church Yard. He is also commemorated on the Casey family grave in Padstow cemetery where family members continue to be laid to rest up to the present day.

Descendants of Sarah Ann Casey who married a Richard Mabley regularly visit Padstow. Pat Dix and Betty Hoskin and members of their families have happily shared family history information with Padstow Museum.

In 1901 Eliza then aged 65 was still living in Padstow along with Gertrude aged 29. Emily (31) Ida (29) and Mary (34) were all working as Drapers Assistants in Hackney. Eliza died in 1914 aged 83 having outlived her husband by 34 years and also her two sons and one of the daughters. Emily returned to live in Duke St Padstow with Gertrude; she was buried in 1941 aged 74. Gertrude lived on ‘til 1961 when she was 84. The last of the Casey’s in Padstow.

The story lives on thanks in part to that Padstow Echo reprint and to a fine old sea chest in Padstow Museum that bears the name JANE LOWDEN. It was donated by Reg Gill of Padstow and we have no reason to doubt that it had once belonged to the ship.

Also the museum has two volumes of a Naval Gazetteer once belonging to John Casey. There are childhood scribbling's from the younger Casey’s in the flyleaves and notes in the margins by the Captain himself. These passed on to us by the late Arthur Permewan.

One reason the story stands out is the reference by Captain Casey of the practice of drinking human blood in order to survive. He claims to have resisted the temptation and refused to allow members of the crew to take this action. In the circumstances few would have blamed him if he did so

In his book ‘Custom of the Sea’ Neil Hanson explores the

fate of the crew of the Mignonette and Richard Parker aged 17. A memorial in his memory has the

quotation from Acts ‘Lord lay not this sin on their charge’. This case came to court in 1884 some

years after the Jane Lowden Story which was one of many to bear the suggestion of cannibalism. The

question, as always, what would any of us do in a similar situation?

Sources.

THE WRECK OF THE JANE LOWDEN

At a time then, when all was revelry and mirth amongst us, and every heart was overflowing with happiness and content, a far far different scene was being enacted on the broad and angry ocean not far from our native shores. We all remember the fearful tidings of ship-wreck, woe and desolation, that came pouring in upon us day after day during those awful winter gales, each tale seeming more terrible than the last, and eclipsing in harrowing details all other such stories ever known.

Few will ever forget the history of the ill-fated “LONDON” and her human cargo, all (with exception of a small boats crew) engulfed in a few moments beneath the angry billows, and whilst the story was yet fresh in our minds, came the whisper of the water-logged ship, the mere carcase of a vessel, having been found drifting about in mid ocean, with a solitary man, in an exhausted condition, lashed in what had once been the main top of the stately ship (now, alas, a mere beacon of distress and famine, and death), which it had been his ill fate to command.

This unfortunate was found to have been a whole month

without a morsel of food; and was from constant exposure to cold and wet, a complete cripple. It is

the story of Captain John Casey, the only survivor of eight ships’ all leaving Quebec together, that

we now purpose placing before the reader; and to the render it the more interesting we give the

narrative in the Captain’s own blunt straightforward words. Before proceeding, however, let us give a

brief description of the vessel and her belongings:-

The JANE LOWDEN was a barque of 581 tons, and

was owned by Thomas Seaton Esq; of Padstow; was built in North America in the year 1848, and had been

employed in the Coast of Africa and Quebec timber trade. She was well manned and well found, and

considered by all as a good trustworthy ship.

Her crew consisted

of:-

Captain John Casey

Edwin Mabley, Mate

James Bird, Second Mate;

James

Beat, Carpenter,

John Avery, Cook and Steward

Francis Martin, A.B,

William Thomas A.B.

High Rice. A.B.

John Connolly A.B.

John Pugh A.B.

Thomas Bowen A.B,

Henry Pope

A.B

James Griffin A.B.

Thomas Geak

Alfred Bolton

Boy Seamen-:

She left Milford in August. 1865, and after rather a long

passage, arrived in Quebec in November of the same year, and commenced loading with timber &

coal

We left Quebec on the 28th November, bound to Falmouth. We had a fair wind (westerly) down

the St. Lawrence, and our passage down was only relieved, by one incident. One of my men, Thomas

Bowen, had been left behind by accident and as we were passing down the river he came alongside in the

police boat, and at the same time a lad named Alfred came on board and hid himself away, and I did not

discover it till we got to sea.

I do not know his real name but his story was that his

parents were weavers at Bolton (and therefore I always called him Alfred Bolton) ,he had run away in

one of the Cunard boats to Quebec, and there went up the Country and stayed with a farmer at 10/- a

week, who cruelly beat him; and he at length ran away, and managed to get on board as I have

described.

The same Westerly wind favoured us from November 29 until December 4, when we discharged

the pilot at Bic Island.

The next day 5th the wind changed to the Eastward and blew hard, accompanied by a heavy fall of snow. At this time the ship was under easy sail, and every precaution was used to guard against the dangers that usually attend navigation in the Gulf of St. Laurence.

On the 6th the weather slightly moderated, and with a favourable wind we were enabled to proceed on our voyage. On 7th, 8th and 9th – those threatening days which I now recall to my mind as the forunner of the difficulties which afterwards occurred, but which I could then neither foresee nor apprehend – the wind increased to a continuous gale from the N.W. with heavy snow.

The ship, in consequence, now became heavily encumbered both in rigging and hull. We had not yet cleared the gulf, and the dead weight upon her was so excessive that she became quite unmanageable. We succeeded, however, in heaving to under the close reefed main topsail. During this period my chief mate, Edwin Mabley, rendered me great service by his steady attention to duty and to the active fulfilment of my orders.

Fortunately we cleared the coast of New Foundland on

the 10th December but I must observe that, while the JANE LOWDEN was clearing the iron-bound and

inhospitable shore (perhaps not in hospitable in the common adaption of the word), one deviation from

the line of duty on the part of myself or crew, would inevitable have consigned us to instantaneous

destruction upon the flinty rocks.

The morning of the 10th dawned upon us with a considerable

amount of snow and frost. The snow falling upon the crew on duty and freezing upon their clothing

seemed to throw a somewhat lethargic influence upon their senses, although they all worked apparently

steadily according to orders.

The banks of Newfoundland, which we passed on the 11th December,

showed us a continuance of bad weather. The ship was much strained b the violence of the storm, and

the men were obliged to be kept at the pumps night and day, as we discovered she had sprung a small

leak, and it was necessary to keep her well clear of water. This state of things continued until the

20th, the wind blowing from the North East, and the ship making but little way.

About Noon on the 20th the wind suddenly shifted to the S. W. and commenced blowing harder than ever, with the barometer falling fast. However, it was a fair wind, and getting her before it, we, bowled off some nine knots an hour, under close reefed topsail and foresail. The gale increased until the following day, when it blew a complete hurricane, the barometer falling to 28 deg. 40 min.

The wind then veered round again to the N.N.W., and obliged us to take in the main topsail and run before it. At this time the whole of the crew were lashed to the pumps and we had five feet of water in the hold from the sea constantly breaking over us, and the leak increasing. At 4p.m. tried to take in the fore topsail, which blew to ribbons, and whilst the men were still aloft endeavouring to save the wreck of sail, the ship suddenly broached to, and a heavy sea washed away our three boats and all our fresh water (stowed on deck in casks). I immediately ordered the men to cut away the fore sail and haul out the foot of the main trysail to keep her to the wind, as, despite all our exertions, we could not again get her before it.

At 6 p.m. she was completely filled with water. I ordered all hands away from the pumps, and they came to me to ask what they were to do. I told them to collect all the provisions they could, and get into the main-top. This they did, and about 8 p.m. we all mounted there after lashing the helm. Then followed and awful night. The ship lay over with her yard arms in the water, the sea making clear breaches over her, and we expecting every moment she would go to pieces. We were 17 to number, and completely filled the main-top, but there was one great benefit in this – that we assisted to keep one another warm. Fortunately, we had all wrapped ourselves up warmly – each with one or two suits of clothes on (we had no spirits in the ship), some days before, when the bad weather commenced, or we should have perished immediately of cold.

We had plenty of food, but no one thought of tasting it; we were too anxious and wretched then to be hungry, but we huddled together in silence until day. At 10a.m. the gale moderated, and we were able to descend and secure some more provisions; but at 4 p.m. it again increased and drove us aloft. At 6 p.m. during a terrific squall the ship was thrown on her beam ends, with the masts flat in the water. All hands were immediately washed out of the top, and nine of them at once met with a watery grave:- Edwin Mabley, James Bird, John Avery, John Pugh, John Connolly, Thomas Geak, James Griffin, Evan Davis and Henry Pope. The remainder, after a hard struggle, succeeded in getting on the broadside of the ship.

The horrors of this moment can hardly be imagined, far less described – the fearful screams of our drowning companions, the melancholy groaning’s of those who were saved, the creaking and cashing of the ship, and the angry roar of the waves, all combined together, with the pitchy darkness of the sky, to render our position awful in the extreme.

We remained with difficulty in this position by lashing ourselves to the main chains, whilst the sea washed away the foremast, forecastle, cabin and all deck fixtures. Suddenly, without any previous warning, she righted and we again climbed into the top. Scarcely were we there when we commenced searching for our provisions, but, alas, every vestige was gone, and, with the exception of eight biscuits saturated with salt water, we were without food of any description. We were now almost in despair, for death in another form stared us in the face.

The next day, December 22nd, the whole of the stern of the ship came out in one piece, and the cargo commenced floating out of the hold. We shared on biscuit day by day until the 25th, when the last morsels were distributed (Christmas Day). At this moment a sail was discovered standing towards us about three miles distant, and we immediately commenced making signals of distress, we had saved the ships ensign, and hoisting this reversed we hoped to attract their attention, and in fact, so far were we convinced of our being seen, that we were actually speculating on the chance of dinner, “and some Christmas pudding too”, as someone jocularly observed, when to our despair and dismay, she passed on without observing us. From that period until the 4th of January 1866, we hardly ever moved or spoke. Our days were passed in praying for night, and our nights in wishing for day.

On this day Alfred Bolton, the boy before mentioned, became

delirious from cold, exposure and hunger, and the effects of drinking salt water, and at length became

so violent that we had to strap him down, to prevent him injuring himself and others.

Two hours

later he became so weak, however, that I ordered him to be cast loose, when he threw himself across my

feet and died; this being the tenth day without food. The next day we committed his body to the

deep.

Two days later (January 6th) William Thomas became delirious, and commenced reciting hymns and calling on his mother for water, and to shut the door to keep the cold out. He sank rapidly, and died the same evening his last word being “Mother”. On the 7th Inst. Thomas Bowen sank and died, and on the following day, Francis Martin, William Maitland, and Hugh Rice. The two former begged to be allowed to eat part of the lads’ body, but this I strictly forbade. There were now remaining only the carpenter and myself, and on the following morning (9th) we lowered the bodies on the deck.

The deck, however, had by this time been; blown up by the water, and the bodies becoming jammed by the washing of the waves got frightfully mutilated. This fearful sight, from which we had no escape, added to the horror and misery of our position, was almost sufficient to drive us to madness. On the 13th inst, about noon, the carpenter said, “How much longer do you think it possible we can live; this is the 18th day without food?” I asked him if he felt strong? He said “he would feel better if he had a drink of water.” We obtained a small portion of lead off the mainmast head, and chewed it to moisten our mouths. We then began to talk, and he asked me to make him a promise that if I survived him and be saved I would acquaint his wife and family of his end. This I readily agreed to do, and made him promise to do the same by me. I tried to rouse him up, but in vain, and he passed quietly away (January 14).

I kept the body by me until the following evening in hopes of breaking the force of the wind. I had then been 60 hours without water, and the temptation to open a vien and drink the blood became very strong within me. When I found this growing upon me, I lowered the body out of the way, where I could not reach it. I remained in this position ten days longer, counting during that period no less than ten vessels, all of which passed me without taking any notice, and one vessel in particular – a brig- passed so near that I could see the people on the deck.

I had placed myself on my back in such a position that my mouth caught some few drops of rain from the rigging as it dripped, and this kept me alive. The agony I suffered in my hands and feet is indescribable and at times my brain seemed wandering, and I seemed to hear strange voices round me at night. Still a strange sort of confidence seemed to possess me that I should be saved, and live to tell my tale.

On the 23rd January at 8 a.m. I found to my intense joy and delight, that a large vessel was close to me, hove to, and which proved to be the Dutch Barque IDA ELIZABETH, OF Rotterdam, from Batavia, and I found that she had been lying by all night and had heard my calls for help, for it had been my practice to shout with all the power left me every few hours in hopes of some vessel passing near and hearing me.

As soon as I saw them I made another effort to shout, and

had the gratification to see them hoist the Dutch ensign and wave to me. In a few moments more a

boat was lowered, and came bounding towards me at the peril of the lives of the five brave men who

manned her.

I made signs to them to come near the bow, fearing lest the water might suck them into

the open stern of the ship; and as soon as I saw them near me I made a tremendous effort, and seizing

the rigging between my arms succeeded in slipping down to the deck from my perilous position. A man

whom I afterwards found to be the boatswain, jumped on board, and lowered me into the boat.

They then pulled back to their ship, and hoisted me up into the boat, after having been 28 days without tasting food of any description. Providentially there was on board an eminent physician of the name of Schruder, who immediately took me in charge, and it is mainly to his care and attention I am indebted for my life. The vessel then made all sail, and we arrived at New Diepee on 31st January. The following day I was admitted to the hospital at the Helder, where I remained until the 11th June suffering amputation of five toes and six fingers, and experienced the utmost kindness from everyone.

I left Helder (a cripple, but thankful to heaven for my life) on 11th June, and embarking at Rotterdam on board the Hamburg STEAMER, ARRIVED IN London on the following day.